COMPLETE BICYCLE Repair Manual

What's Included?

Fast Download Speeds

Online & Offline Access

Access PDF Contents & Bookmarks

Full Search Facility

Print one or all pages of your manual

This chapter has several sections. It should be read

carefully to prepare for using all the other chapters.

The first section is

This section covers only the most

basic and universal terms. The other chapters will

each start with a terminology section with terms that

are more specific.

The second section is Understanding

thread descriptions and thread types is perhaps the

most important basic mechanical skill.

The third section is Press fits are a

means of holding pieces together other than by thread-

ing them. It is a system with its own unique set of

techniques and rules.

The fourth section is Understand-

ing the proper use of greases and oils is critical to be-

ing a good mechanic.

The fourth section is

This section covers what types of cleansers, sol-

vents and polishes might be used, and how to use

them properly.

The last section is This section covers use

of common mechanics tools. The other chapters de-

scribe how to use bicycle mechanic specific tools. A

list of recommended tools is in the appendix.

Chapters on individual component areas of the

bicycle have more specific terminology and definitions.

For the purpose of this manual, the following terms

apply to the frame and basic components.

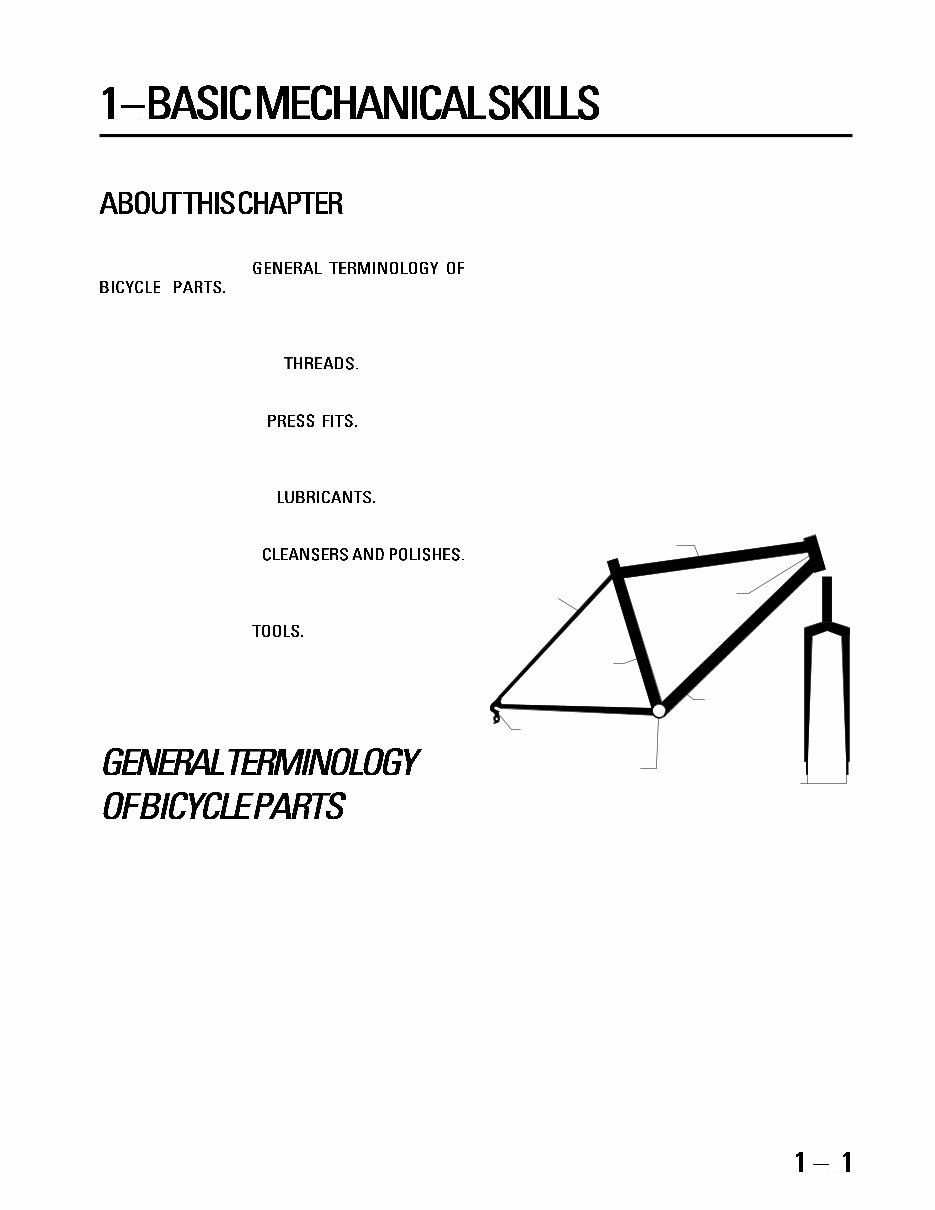

Frame: The structural piece, usually a number of

tubes joined together, to which all of the components

are attached.

Fork: The structural piece that attaches the frame

to the front wheel. The fork turns to allow the rider

to control the bicycle.

Frame set: The frame and fork combination.

Head tube: The near-vertical tube that is the for-

ward most part of the frame.

Top tube: The upper tube of the frame that ex-

tends back from the head tube to the seat tube.

Down tube: The lower tube of the frame that

extends from the bottom of the head tube to the bot-

tom of the frame (the bottom-bracket shell).

Seat tube: The near-vertical tube that is at the

middle of the frame, which the seat post slides into.

Bottom-bracket shell: The portion of the frame

that contains the crankset bearing parts, which are

called the bottom bracket.

Seat stay: The two tubes of the frame that start

from below the seat and meet the chain stays at the

center of the rear wheel.

Chain stay: The two tubes of the frame that go

from the lower end of the seat tube and meet the seat

stays at the center of the rear wheel.

Dropout: The fittings at the end of the fork, and

at the juncture of the seat stays and the chain stays, to

which the wheels are attached.

Top tube

Seat stay

Chain stay

Bottom-bracket shell

Head tube

Down tube

Fork

Dropout

Dropouts

Seat tube

1.1 Parts of the frameset.

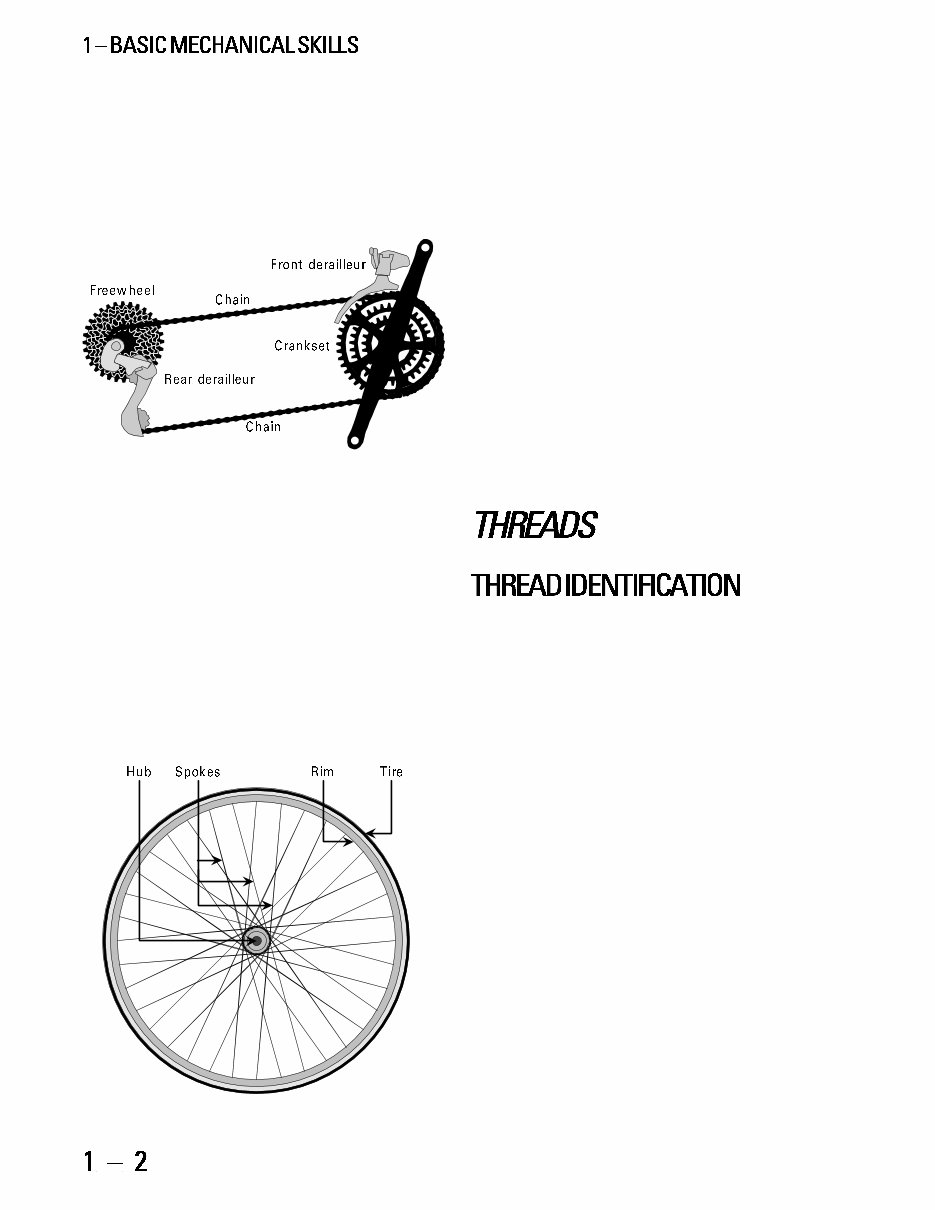

Derailleur: There are two such mechanisms: a

front derailleur and a rear derailleur. The front de-

railleur moves the chain between the selection of gears

on the crankset; the rear derailleur moves the chain

between the selection of gears on the rear wheel.

Chain: The loop of links that connects the front

gears to the rear gears.

Freewheel: The set of rear gears. Freewheels and

freehubs have a confusing overlap of terminology. For

clarification, see the terminology section of the chapter

regarding these items. In a general sense, the freewheel

is the set of gears that the chain turns in order to ap-

ply drive forces to the rear wheel.

Crankset: The mechanism that is turned by the

riders feet. It consists of two lever arms called crank-

arms, one to three gears called chainrings, and a bear-

ing assembly that the crank arms rotate around called

the bottom bracket.

Bottom bracket: The bearing assembly that al-

lows the crankset to rotate in the bottom-bracket shell.

1.2 Parts of the drivetrain.

Wheel: The assembly consisting of the hub,

spokes, rim, tire and tube.

Hub: The assembly at the center of the wheel that

houses the axle bearings, and to which spokes attach.

Freehub: A hub and freewheel that have been

combined into a single integrated assembly.

Spokes: The tensioned wires that join the hub and

rim together.

Rim: The hoop at the outer edge of the wheel to

which the tire is mounted.

Tire: The rubber hoop at the outer edge of the

wheel assembly.

1.3 Parts of the wheel.

Headset: The bearing assembly that connects the

fork to the frame and allows the fork to rotate inside

the head tube.

Pedal: A mechanism that supports the riders

foot. It contains a bearing assembly and is mounted

to the crank arm.

Seat post: The pillar (usually a tube of metal) that

attaches the seat to the frame.

Saddle: The soft structure that supports the

riders posterior.

Stem: The piece that connects the handlebars to

the fork.

Handlebar: The piece that supports the riders

hands and is turned to control the bike.

Brake lever: The levers that are operated by the

riders hands to control the braking function.

Shift lever: The levers operated by the riders

hands that control the derailleurs.

Brake caliper: The mechanisms that squeeze

against the rims to control the bikes speed.

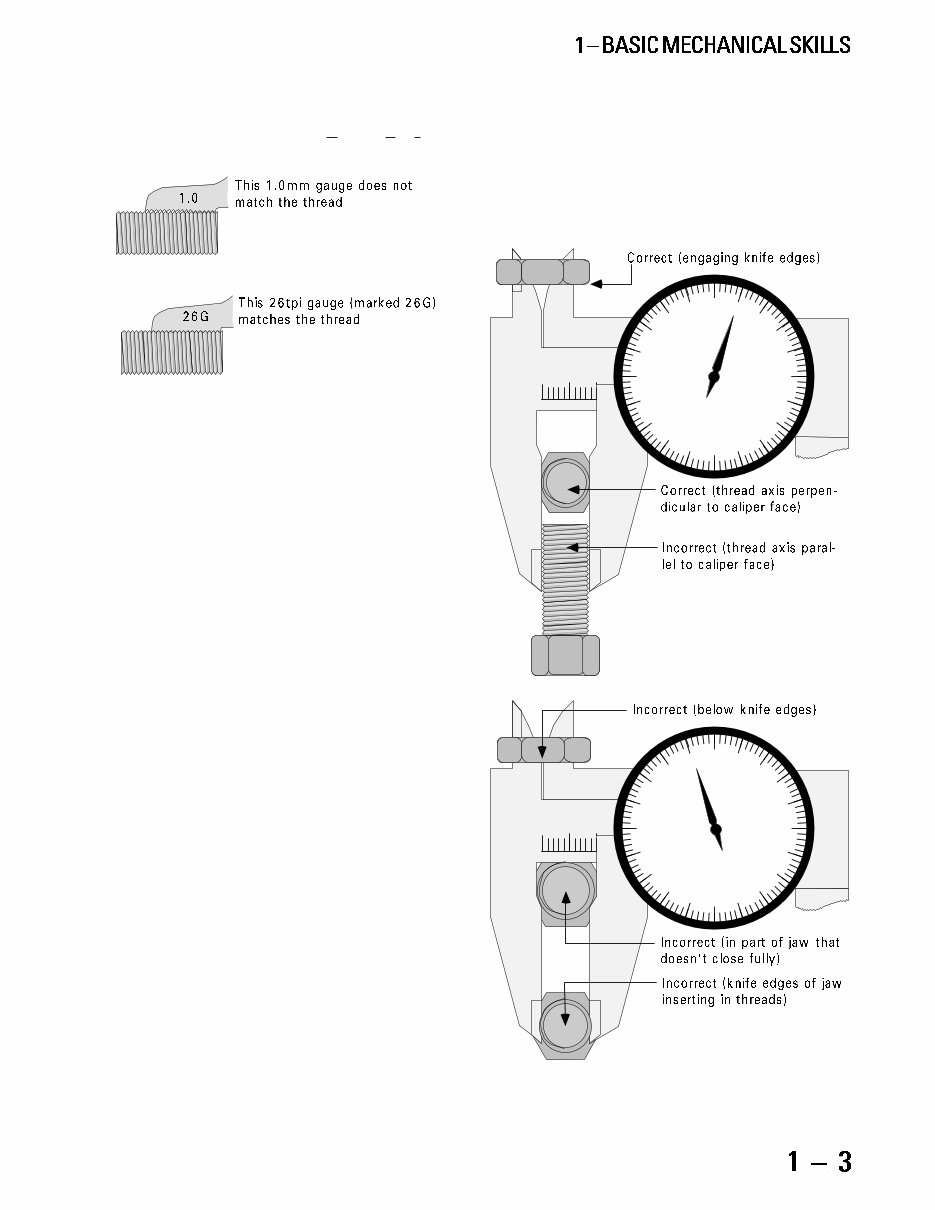

One of the key challenges to the mechanic is to

be able to replace or upgrade parts with compatible

parts. One of the most significant obstacles to be over-

come is the number of different thread standards used

on bicycles. For example rear axles alone come in seven

different varieties. Threads are described by a two part

number, such as 3/8" × 26tpi or 10mm × 1mm. The

first number refers to the diameter of the male ver-

sion of the thread and the second number refers to

the pitch. When identifying a thread, start with pitch.

The first step to identifying a thread is to measure

the pitch with a pitch gauge. Pitch is a measurement of

the frequency of threads, or the distance from one thread

to the next. In an inch system (BSC and Whitworth),

pitch is measured by the number of threads that occur

in one inch of thread length, and in a metric system

pitch is the distance from one thread to the next.

Pitch is measured with a pitch gauge by mating

the gauge to the thread. If the gauge can be held down

in the thread at both ends simultaneously, the thread

is identified (see figure 1.4). The best pitch gauges avail-

able come with both metric and Whitworth gauges.

Although Whitworth is quite rare, Whitworth pitch

gauges are compatible with the BSC (British Standard

Cycle) threads found on many bicycle parts. Although

gauges are not normally marked with the appropriate

units, the thread is metric whenever the number in-

mon BSC freewheel threads. Also, Jou Yu (Joy Tech)

hub axles have metric diameter combined with inch

pitch in some inconsistent cases.

When measuring diameter use a caliper. Measure

the thread with the axis of the thread perpendicular

to the face of the caliper, the axle centered in the cali-

per jaws and not on any slot in the threads.

0 1

0 1

0

0

0

0

.1

.1

.1

.1

.2

.2

.2

.2

.3

.3

.3

.3

.4

.4

.4

.4

.5

.5

.5

.5

.9

.9

.9

.9

.8

.8

.8

.8

.7

.7

.7

.7

.6

.6

.6

.6

1.5 Correct and incorrect ways to measure thread diameter.

cludes a decimal point, and the pitch is in inches when-

ever the number on the gauge is followed by the let-

ter G or the letters TPI (for Threads Per Inch).

1.4 When the teeth of the thread pitch gauge will all go into the

threads simultaneously, then the gauge matches the thread.

The next step to thread identification is to mea-

sure the diameter. Diameter is a measurement of the

male threads outside diameter (O.D.). It is usually a

nominal measurement. A measurement is a nominal

measurement when an actual measurement is rounded

up to an even number. For example, a thread with a

6mm diameter is only nominally 6mm. The actual

diameter is more like 5.9mm.

Metric bicycle threads are available in .5 millime-

ter increments, so always round the actual measure-

ment up to the nearest .5mm to arrive at the nominal

measurement. Inch bicycle threads are available in

minimum 1/16 inch increments, so always round up

to the nearest 1/16 inch or its decimal equivalent to

arrive at the nominal measurement.

Examples:

If the thread measures 5.9mm it is 6.0mm.

If the thread measures .370" it is .375".

If the thread measures 23/64" it is 3/8".

Diameter may be measured in inches or millime-

ters. The best way to determine which units to use is

by measuring the pitch first, because the diameter is

almost always in the same units (a 1.0mm pitch

threaded item is sure to have a metric diameter). The

exceptions are on Italian-manufactured frames, which

have metric diameter and inch pitch on the fork and

in the bottom-bracket shell, and on Italian-made hubs,

which may have metric diameter axles with inch pitch.

Italian bikes will also have this combination of metric

diameter and inch pitch on the freewheel mounting

threads, but in this case it is not an issue because the

Italian thread happens to be compatible with the com-

1.6 Whether the thread slopes up to the left or up to the right shows

the thread direction.

Female threads may be identified as left or right

by the following test. Install a matching thread pitch

gauge into the thread in question with exactly one

tooth of the gauge left outside the thread. Rotate the

gauge in the threads at least one-half turn clockwise.

Observe the amount of gauge teeth outside the thread

at this point. If they have increased, it is a left-hand

thread. If they have decreased, it is a right-hand thread.

If the gauge is rotated counterclockwise instead of

clockwise, the results will be opposite.

1.7 Rotate a thread pitch gauge in a female thread to determine

the thread direction.

It is helpful to know what threads are likely to be

encountered in certain situations. The country of origin

of a bicycle frame is likely to determine the thread used in

the bottom bracket and the fork/headset. Different coun-

tries tend to use different thread standards. The standards

are BSC (British Standard Cycle), Metric, Italian

Whitworth, and ISO. ISO stands for the International

Standards Organization. The ISO has adopted many ex-

isting thread descriptions to be the ISO standard. Some of

these existing threads are metric, and some are BSC. ISO

standard threads may have a metric or inch description.

Bicycle frames made in Taiwan, and Japan are cer-

tain to be BSC or ISO thread. Bicycle frames made in

the U.S. are also virtually certain to be BSC or ISO thread,

but sometimes small manufacturers of top end racing

bikes use Italian threads. Bicycle frames made in Italy are

virtually certain to be Italian thread. French bicycles are

the greatest source of confusion because they used to be

French thread, then switched to Swiss thread, and fi-

nally have switched to ISO threading. Bicycle frames from

other countries are seen much more rarely, and it is best

to rely strictly on measurements in these cases. See the

bottom bracket and headset chapters for description of

BSC, ISO, French, Swiss, and Italian threads.

Female thread diameters are rarely provided.

When the pitch is 24tpi, 26tpi, or 1mm the inside

diameter will be approximately .7.9mm less than

the male.

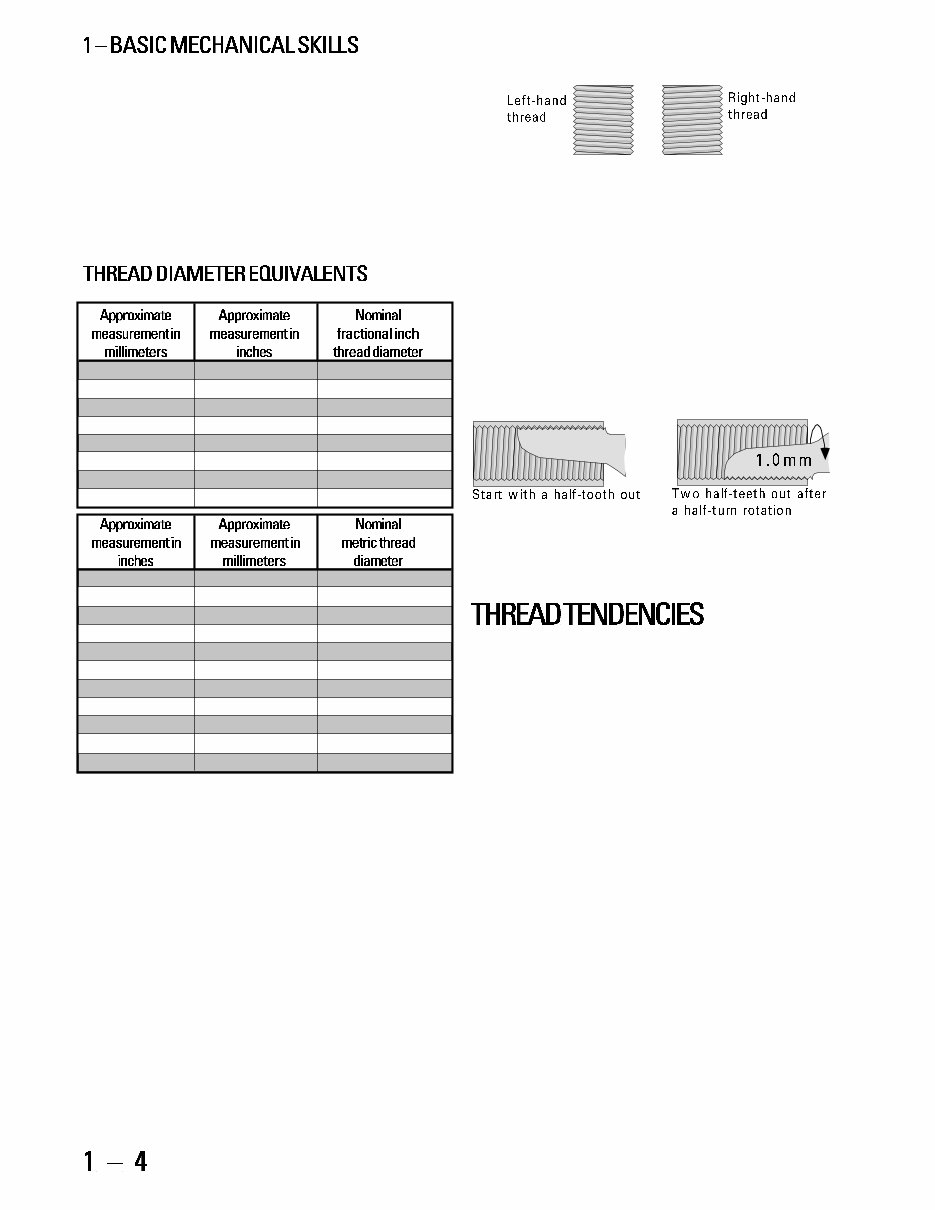

Following is a chart of useful equivalents of thread

diameter. Start by taking a measurement in inches or

millimeters and then look in the right-most column

for the nominal thread diameter.

(table 1-1)

7.7mm .303" 5/16"

9.4mm .366" 3/8"

12.5mm .492" 1/2"

14.1mm .555" 9/16"

25.2mm .992" 1"

28.4mm 1.118" 1–1/8"

31.6mm 1.244" 1–1/4"

34.7mm 1.366" 1–3/8"

.149" 3.8mm 4.0mm

.189" 4.8mm 5.0mm

.228" 5.8mm 6.0mm

.307" 7.8mm 8.0mm

.351" 8.8mm 9.0mm

.346" 9.3mm 9.5mm

.389" 9.8mm 10.0mm

.976" 24.8mm 25.0mm

1.358" 34.5mm 34.7mm

1.370" 34.8mm 35.0mm

1.409" 35.8mm 36.0mm

On all pedals and most bottom-bracket threads

(as well as other rare occurrences), the final aspect of

thread identification is the thread direction. Right-hand

threads (most common) tighten or are installed with a

clockwise rotation and loosen or are removed with a

counterclockwise rotation. Left-hand threads (left ped-

als, some right-hand-side bottom-bracket parts, and

certain freewheel cones and dust caps) tighten or are

installed with a counterclockwise rotation and loosen

or are removed with a clockwise rotation.

Thread direction of male threads may be identi-

fied by observation. Held vertically, the threads on a

right-hand thread will slope up to the right, and the

threads on a left-hand thread will slope up to the left

(see figure 1.6).

The country of origin of a component is useful in

determining the thread type of fittings within the compo-

nent, but the threads that attach a component to another

component or the frame may be unrelated to the country

of origin. For example a bottom bracket made in Japan

for an Italian bicycle would be Italian thread. Another

example would be that an Italian made freewheel installed

as original equipment on an older French bicycle would

probably be a French thread. The threads used within

any Japanese, Taiwanese, or French component are likely

to be metric. The threads used within any Italian compo-

nent are likely to be metric or Italian Whitworth (a bi-

zarre combination of metric diameter and inch pitch).

There is little consistency with U.S. component manufac-

turers to use metric or inch threads. Those U.S. compo-

nent manufacturers that contract to have their products

made in Asia are more likely to use metric threads. For

example, Grip Shift uses metric threads on fittings, but

fittings on Bullseye hubs use inch pitch threads.

The primary form of thread preparation is lubri-

cation. Preparation of threads with oil or grease per-

mits ease of assembly and disassembly. Lubrication

makes it easier to feel when the threaded component

is becoming tight enough. Corrosion is also prevented

by lubrication; however, lubrication is counter effec-

tive on threads with nylon inserts.

In most cases the lubrication choice is between oil

and grease. Oil is generally used on threads of small

diameter or fine pitch. Ease of application is the pri-

mary advantage compared to grease. Grease is used

on threads of larger diameter and coarser threads. Its

advantage over oil is durability under exposure to

moisture and less of a tendency to evaporate.

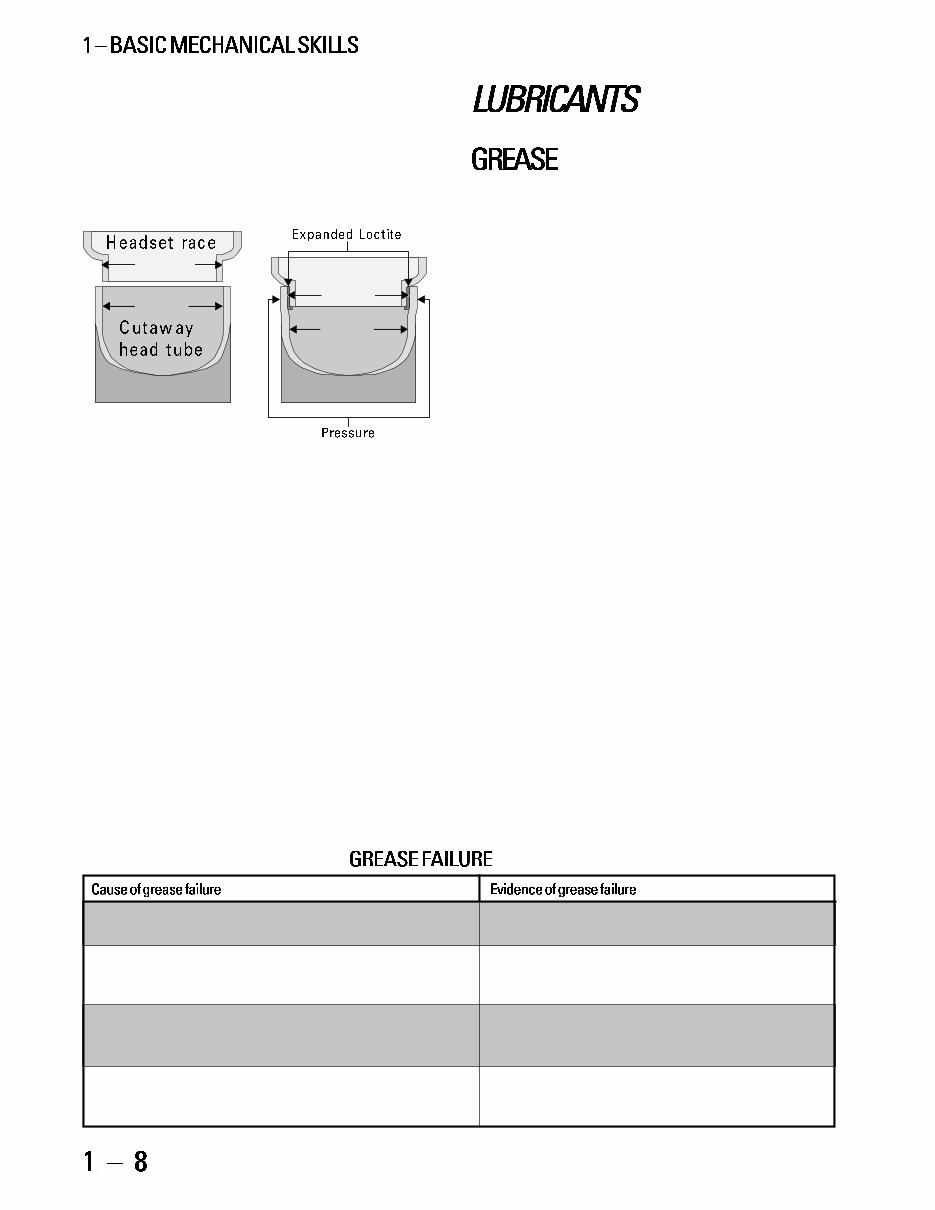

In some cases it is preferable to use a compound called

Loctite instead of lubrication. Loctite is a liquid that hard-

ens and expands after application. It is not a glue, but

works by expanding to fill a gap and exerting pressure

between the parts. Loctite used on threads aids ease of

assembly, prevents corrosion, prevents threaded com-

ponents from coming loose and consequentially reduces

the need to over-tighten parts, risking their damage.

Loctites generally cure in a few hours. The hard cake

that Loctite compounds cure into is not an adhesive. The

hard cake deteriorates if the threaded item is turned after

curing. Use of Loctite is redundant on threads with ny-

lon inserts. (Loctite is toxic minimize contact.)

There are several grades of Loctite. Some of the

following grades are available from automotive stores

or United Bicycle Tool Supply, but some must be

purchased at industrial bearing supply companies.

Loctite 222 is the lightest grade available and is ap-

plicable on thread diameters up to 6mm. Typical uses

of Loctite 222 include: accessory mounting bolts/nuts,

brake mounting bolts/nuts, and derailleur limit screws.

If only one grade of Loctite were to be used, it

should be Loctite 242. It is heavier than the 222, and

is used on larger diameter threads. Typical uses of

Loctite 242 include bottom-bracket fixed cups and

headset locknuts, but it is also acceptable to use it on

smaller thread diameters.

Loctite 290 is a special application thread locker

that is more heavy-duty than 242, but can be applied

to already assembled components to penetrate into

the threads. Typical uses of Loctite 290 include already

installed accessories (such as fenders) and already in-

stalled bottom-bracket fixed cups.

Loctite 272 or 277 are extremely heavy-duty com-

pounds that would not allow removal without dam-

age to the tool or part. They are used when threads

are damaged and as an alternative to replacement when

permanent installation will not be a problem.

Loctite RC680 serves as a substitute for 272/277

and can be used in other non-thread applications on

the bike, such as enhancing the security of a pressed-

in part like a headset cup.

Loctite 660 (Quick Metal) is not applicable to threads

at all, but will fill gaps for press fits of up to .5mm.

When assembling threads pay close attention to

how they feel. Threads that feel tight during assem-

bly should be checked for:

Thread compatibility

Paint in threads (Clean with tap.)

Damaged threads (Clean with tap, die, thread

chaser or file.)

Cross-threading (Restart thread with better

alignment.)

That threads feel effortless to assemble is not by it-

self an indication of thread compatibility. When the fe-

male thread is a larger diameter than the male, no effort

will be required for assembly, even when there is a pitch

mismatch. If pitch match has not been verified but the

difference between the O.D and I.D. of the parts is ac-

ceptable, then it is acceptable to use test-mating of parts

as a way to determine compatibility. This is a useful tech-

nique in cases where it is impractical to check the pitch

because of small I.D., or short overall thread length.

A thread that gets tight and then feels easier to

turn as it is secured is probably stripping.

Ideally, when threads are damaged the part should

be replaced. If tools are available and the damage is

not too severe, it may be possible to repair the thread.

The best repair will be accomplished with a thread

cutting tool such as a tap (for internal threads) or die

(for external threads). When repairing threads with a

tap or die, first make sure the damaged thread and tap

or die have compatible thread description. Start the

tap or die on the end of the threaded item that is in

the best condition to ensure proper alignment.

If the die is a variety with a split in it so it can be

compressed or expanded, it should be fit in a special

die handle that has expansion and compression adjust-

ers. Thread the die onto the good portion of the thread

with it expanded to a loose fit. Then compress it until

it is barely snug before starting to cut on the threads

that need repair.

An alternative to using a tap or die is to use a thread

chaser. A thread chaser does not actually cut threads.

It does realign threads that have been mangled. It is

most often used on solid axles or the dustcap threads

in crank arms.

The least expensive way to repair a thread is with

a thread file. The thread file is best when there is just

a small ding in a thread. Thread files can be used on

mangled male threads. Available from various bicycle

tool and general tool suppliers, thread files come in

both inch and metric pitches. After matching the pitch

on the file to the pitch of the thread being repaired,

the file is then stroked in the direction of the thread

angle, while the item being repaired is slowly rotated.

1.8 To use a thread file, match the file pitch to the thread pitch,

then stroke the file at the angle of the thread while rotating the

threaded item.

Stripped threads can sometimes be repaired just

by chasing them with the appropriate tap, die, or

thread chaser. If the thread still does not hold after

this repair, repair options include use of Loctite 277

or RC680, drilling the damaged thread out to a larger

diameter and re-tapping to use a new size, or replac-

ing the damaged part. Using Loctite is a solution only

when there is no further need to remove the part.

Converting to a larger diameter thread may be lim-

ited by available material or parts. Replacing the dam-

aged part has no disadvantage, except cost or limita-

tions of availability.

To repair a stripped thread by going to the next larger

diameter, first drill out the old threads to the appropri-

ate size for the tap that will create the new thread. When

drilling to tap, the use of a larger bit than recommended

will lead to poor thread depth and will probably result

in further thread failure. The use of a smaller bit than

recommended will result in the tap jamming and break-

ing off in the hole. To determine the correct drill size a

simple formula can be used. If it is a metric thread, sub-

tract the pitch from the nominal diameter of the thread;

for example, converting a stripped 4.5mm × .8mm fe-

male thread to 5mm × .8mm requires drilling the hole

out to 4.2mm (5.0 .8 = 4.2). Another example: the

correct tap drill for tapping a 6mm × 1mm thread would

be 5mm (6 1 = 5). For inch thread (which is unlikely

to be needed due to the rare use on inch threads on bi-

cycles), a special or unusual drill bit size is needed. Inch

size threads require tap drills which are unique sizes

that are numbered instead of described by dimension.

After drilling out the hole use the appropriate tap for the

new thread size.

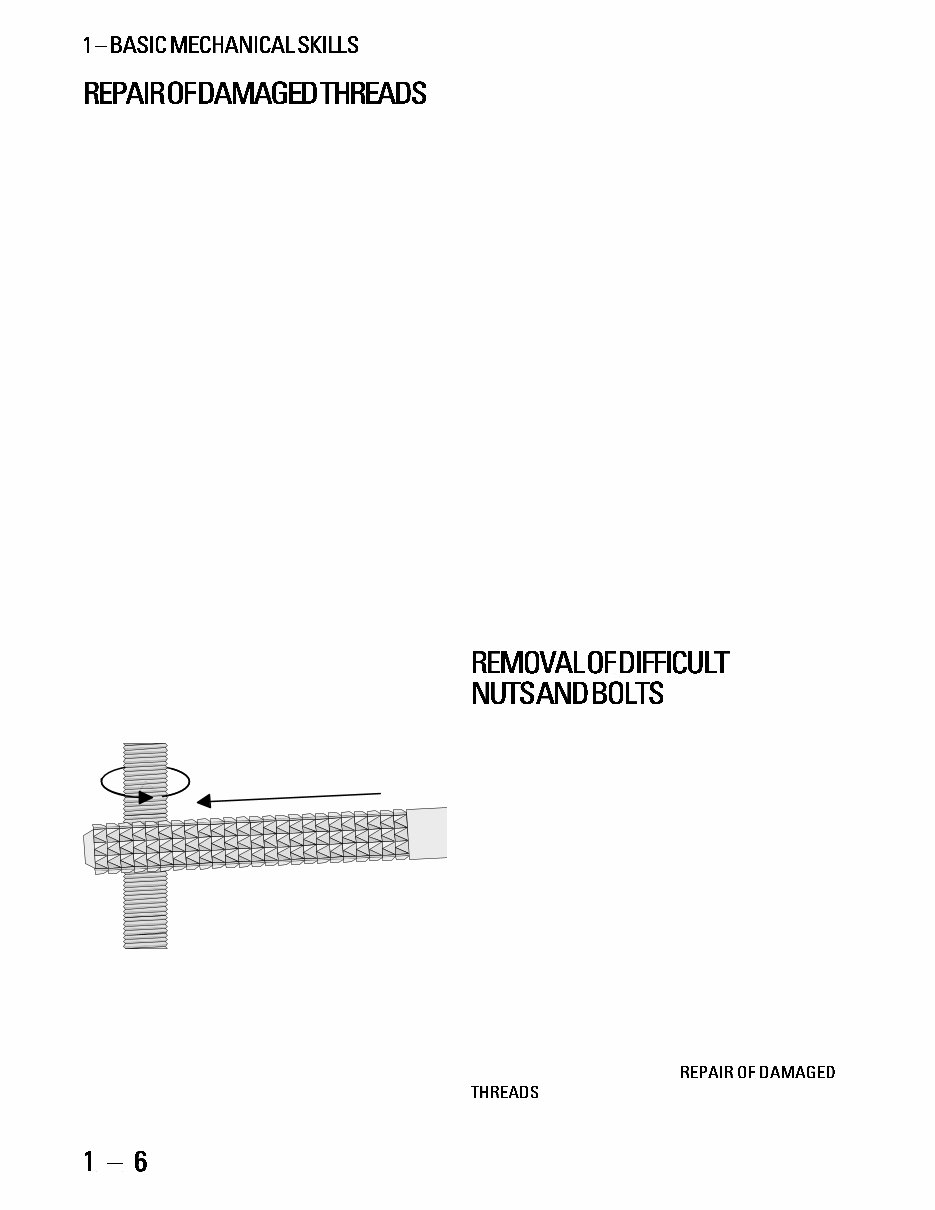

To remove a stubborn nut or bolt first use a pen-

etrating oil and allow to soak for a few minutes. Then

use the best-fitting tool possible. If it is a screwdriver,

apply heavy, downward force while turning the screw.

If a screw or bolt head is deformed in the attempt to

remove it, try vise grips locked securely on the head. If

vise grips fail, use a small saw (Dremel or rotary tool)

to cut a slot in the head to fit a slotted screwdriver.

Another alternative is to file flats on the side of the bolt

or nut head to fit an open-end wrench. If all of the

above fail, the next option is to drill a hole in the bolt

or screw between one-half and three-quarters of the bolt

diameter and then hammer in a screw extractor to turn

out the bolt. The screw extractor is the first option if

the screw or bolt head shears off. The last resort is to

carefully drill the bolt out with the tap drill that is the

appropriate size for the existing thread diameter. The

method for determine the correct size for the drill bit is

covered in the preceding section,

. Then chase the threads out with a tap.

To remove a stripped nut, screw, or bolt that ro-

tates without removing first use penetrating oil. If

possible, grab nut, screw, or bolt with vise grip to pull

up while unthreading. Another alternative is to insert

something like a screwdriver underneath the nut or

screw or bolt head and apply leverage while

unthreading. The last alternative is to use a saw to cut

off the nut, screw, or bolt head.

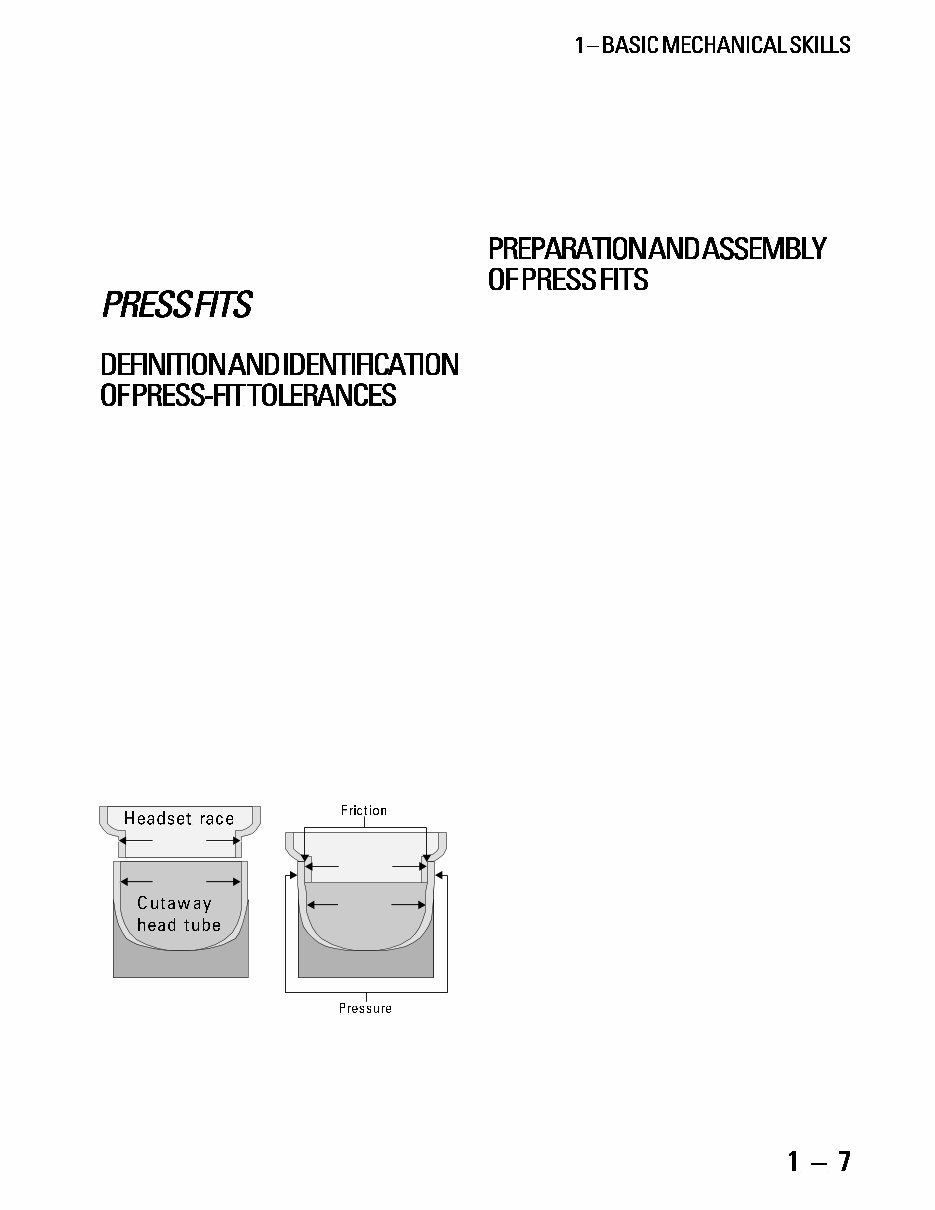

A press fit occurs when one part is inserted into

another with pressure and is held together by the fric-

tion between the mating surfaces.

A common press fit is the interference type. With

an interference type, the fit is accomplished when a

male cylindrical shape is pressed into a smaller hole.

The tolerance between the two parts is generally in

the range of .1.3mm (.004.012"). Examples of inter-

ference press fits include:

Headset races pressed into the head tube

Headset race pressed onto the fork

Dustcaps pressed into hub shells and pedals

Bottom-bracket bearing cartridges pressed into

a bottom-bracket shell

Bearing cups pressed into hub shells and pedals

Cartridge bearings pressed into bottom brack-

ets and hubs

Cartridge bearings pressed into pedals

30.2mm

30.0mm

30.0mm

30.2mm

1.9 These cross-sections show a properly sized headset race before

installation into a head tube, and again after the head tube has de-

flected to accommodate the press fit.

Another type of press fit is the tapered press fit.

In this case the male component is tapered so that the

farther it is pressed in, the tighter it becomes. Examples

of this fit include:

Cotter pins on cotter-type crank arms

Cotterless crank arms that fit on a spindle with

tapered flats

Preparation to install a press fit should include

identifying that the male component is a suitable

amount larger than the female; cleaning the mating

surfaces so that they will be free of lubrication, corro-

sion, and dirt; and treatment with Loctite 222 if pre-

venting corrosion is a concern.

To install press-fit components, a special pressing

tool is often required (see the section of the book that

applies to the particular component in question.) In

the absence of a proper tool, sometimes a vise can be

used, and if that is not suitable, a hammer may be

used. In either case, pay particular attention to the

alignment of the parts as they go in. With a hammer,

use a block of wood or a plastic hammer to protect

the components from damage. With a vise, similar

types of protection may also be required.

Proper installation of tapered-press fits simply

involves pressing the part in hard enough so that it

will hold. Preparation to install tapered-press fits

includes an examination to determine that the length

of engagement is acceptable and cleaning the mat-

ing surfaces, so that they will be free of lubricants,

corrosion and dirt.

For more information and diagrams concerning

tapered press fits see the section of this book regard-

ing crank arms.

When press fits slip together with little or no ef-

fort, Loctite compounds may be used to improve the

fit. If the fit requires only mild force to install, it will

probably creak or slip under operating conditions, or

moisture may penetrate and cause corrosion, then the

use of Loctite RC680 would be appropriate in most

cases. When installing sealed cartridge bearings (hubs,

bottom brackets, and pedals) Loctite 242 is preferred,

so that removal will not be too difficult. If a press-fit

part slips right in with no effort, but does not jiggle

about once installed, then Loctite RC680 is required

in all cases except for sealed cartridge bearings. Sealed

cartridge bearing installation requires Loctite 242, usu-

ally. If Loctite RC680 is used to improve a marginal

press fit, the fit should be considered as good as new,

except that removal and reinstallation would require

re-application of Loctite. If the press-fit part is loose

Not all greases are suitable for bicycle use. Bicycle

bearings operate in a relatively low temperature range,

so grease designed for automotive use often does not

become effective at bicycle operating temperatures.

Greases made specifically for bicycle use include Phil

Wood, Bullshot, Var, Shimano, Finish Line, Pedros

and Campagnolo. The best automotive grease is a light

grade of Lubriplate.

Grease failure could come at any time. Factory

original greases are often of the lowest quality, and

also are applied in very limited or erratic quantities.

Frames are often inadequately cleaned at the factory,

so bottom-bracket and headset grease is often con-

taminated with abrasives even before the bike has

been ridden. For these reasons it is difficult to project

the normal time or miles between bearing overhauls.

As a soft rule of thumb, 20003000 miles or two to

three years of generally fair-weather riding should

make a bike ready for an overhaul. The best method

to determine whether grease is overdue for replace-

ment is inspection. See table 1-2 below, for causes

and evidence of grease failure.

The container and applicator of grease is as im-

portant as the quality. Open tubs invite contamina-

tion; application from open tubs is messy. Grease is

best used in squeeze tubes or grease guns.

Whether greasing a thread, insertion, or bearing,

an ample quantity of grease will reduce likelihood of

drying and moisture contamination. Wipe excesses

away when assembly is complete.

Grease should be treated like any other unnatural

substance that can penetrate the skin. Minimize expo-

sure or avoid it entirely by wearing disposable latex

painters gloves. Clean hands when exposure is over.

and jiggling after installation, it is best to find a better

fitting part. If a better fitting part is not available,

Loctite RC680 is recommended. Effectiveness may be

limited by how loose the parts are initially, and the

by fact that with press fitting there is no way to en-

sure proper alignment of the parts.

30.05mm

30.0mm

30.0mm

30.2mm

1.10 The headset race and headtube here do not have enough di-

mensional difference to create enough friction; when Loctite RC680

is added before installation, it expands and creates more pressure

(and therefore more friction).

Loctite 660 (Quick Metal) is a thick paste that will

provide security when the male part is up to 1mm

smaller in diameter than the female part. No preci-

sion alignment of the parts is assured, but loose pieces

that cannot be repaired in any other way may benefit

from Quick Metal. A good example would be when

the head tube on a Murray or Huffy juvenile bike

becomes flared and the headset parts are loose and jig-

gling. Because these bikes use non-standard oversized

headset dimensions, there are no practical alternatives

for repair except the use of Loctite 660 (Quick Metal).

(table 1-2)

Age: This is one of the most likely reasons for grease Lack of grease, grease absent from ball path,

to fail, particularly on bikes that see little use. grease caked like half-dry mud.

Internal contamination: This other highly likely cause Light-colored greases turned dark, translucent

of grease failure is caused by particles worn from the greases turned darker and opaque.

bearing surfaces.

Moisture contamination: This cause is only likely Reddish rust color in grease, rust on bearing

when the bike is ridden extensively in wet conditions. parts, water droplets in grease or bearing area.

Colored greases turn a lighter shade.

Dirt contamination: This cause of grease failure is Gritty feeling like sand in the grease, not the

most likely if contaminated grease that has oozed out same as the rough feeling from a tight bearing.

of the bearing is wiped off the wrong way.

Manufacturers of internally-geared hubs recom-

mend special oils that are generally unsuitable for use

elsewhere on the bike. Sturmey Archer Cycle Oil is

one of these, but a suitable replacement would be 10-

weight motor oil.

One of the cleansers needed for proper bicycle

cleaning is an ammonia and water solution for clean-

ing dirt and removing greasy fingerprints. If using a

household cleanser such as 409, Fantastik, or Top Job,

they will leave a soapy film that will need rinsing.

Window-cleaning compounds clean as well and do not

leave a film behind.

For cleaning bearings, drive train components and

any other heavily greased or oily components, choose

between either mineral spirits or non-toxic biodegrad-

able solvents (such as citrus-based solvents.) These are

the environmentally correct alternative to gasoline and

kerosene. If using mineral spirits, avoid excess con-

tact with skin, eyes, and fumes by wearing rubber

gloves, safety goggles, and by working in a well venti-

lated area. Mineral spirits and citrus-based solvents

leave an oily film and are not suitable as a last prepara-

tion before assembling a press fit. Drying time (of

mineral spirits or biodegradable solvents) in confined

areas such as inside chains, freewheels, derailleur and

brake pivots, is quite slow and generally is aided by

blowing with compressed air. If using a biodegradable

solvent, remember that once it is contaminated with

oil or grease it is no longer environmentally friendly.

For certain uses, a more heavy duty solvent (such

as acetone) is needed. Use acetone or rubbing alcohol

when an oil-free surface is required (press fits, braking

surfaces). Use acetone on extremely stubborn dry grease.

Both acetone and alcohol are highly flammable and

volatile, so do not use them around flames or high heat

sources (no smoking). Avoid skin and eye exposure,

and keep fumes to a minimum by disposing of soaked

rags promptly in a fire-safe self-closing metal bucket.

Alcohol is far more environmentally friendly than ac-

etone. There are no biodegradable-type solvents that

perform the same function as these two compounds.

Wax or polish is used to improve the appearance of

paint jobs and to protect them. Most automotive waxes

are suitable for bicycles. Wax should be applied to clean

surfaces with light rubbing. After it dries it should be

wiped off with a soft cloth. Check the label of any au-

tomotive product before using it on the painted surface

of a bicycle. Test products of uncertain suitability on

the bottom of the bottom-bracket shell.

Oil is used on threads, derailleur pivots, brake piv-

ots, lever pivots, the chain, inside freewheels and in-

side internally-geared multispeed hubs.

Not all oils are equally suitable for bicycle use.

The oil needs to be resistant to accumulating grit, du-

rable to exposure to the elements, and light enough to

penetrate into tight areas. These characteristics out-

weigh the significance of any more technical consid-

erations, such as the type of oil base or whether Teflon

is part of the formula. Oils that are specifically suit-

able to bicycle use include:

Phil Wood Tenacious Oil

Triflow

Bullshot

Superlube

Campagnolo

Allsop

Finish Line

Pedros

Lube Wax

The oils at the top of this list are generally more

suited to use in wet conditions while oils that appear

lower down on the list are more suitable for use in

dry, dusty conditions.

Popular oils that are specifically unsuitable for

most bicycle applications include:

WD40

Sewing machine or gun oil

3-in-1 oil

Motor oil

Method of application is very important with oils.

Aerosols are environmentally unfriendly and usually

lead to excessive application. The only exception to

the problem of excessive application is with spray lu-

bricants that are designed to dry in a matter of min-

utes after application (such as Finish Line and Allsop

oils), but these may be the worst offenders environ-

mentally. In general, oils used in external applications

should be used sparingly to avoid dripping and dirt

accumulation, and excesses should always be wiped

off immediately. Overall, the best form of applica-

tion is from drip applicators. They are economical to

use as well, because waste is limited.

In addition to their value as lubrication, oils are

also used to facilitate disassembling frozen threaded

components. Special penetrating oils perform this

function best. Triflow, Allsop, and some other bicycle

oils are somewhat effective for penetration.

This section covers the proper use of common tools

that are not unique to bicycle mechanics. This section

also covers the use of the bicycle repair stand. There is

a comprehensive list of common tools and bicycle spe-

cific tools in the appendix. The types of tools and con-

cepts covered in this section are as follows:

Box- and open-end wrenches

Ratchet drives and sockets

Torque and torque wrenches

Adjustable wrenches

Pliers and vise grips

Screwdrivers

Utilizing mechanical advantage

Hammers

Hacksaws

Files

Grinder

Drilling

Taps

Using repair stands

Always use the smallest wrench that will fit. A

16mm cone wrench seems to fit on a hub cone with

15mm flats, but a 15mm wrench is the smallest that

will fit. It may be possible to turn a 15mm cone with

a 16mm wrench, but it is likely to damage the nut and

the wrench.

Box- and open-end wrenches are non-adjustable

wrenches that are made in specific sizes that are sup-

posed to closely match the fittings they will be used on.

They come in inch and metric sizes. Metric sizes are

most common for bicycles. Certain inch and metric

sizes are interchangeable in one direction only (because

the substitute is only slightly over-sized). These are:

13mm wrench on 1/2" fitting

14mm wrench on 9/16" fitting

16mm wrench on 5/8" fitting

Open-end wrenches contact the fitting at only two

points, making them inclined to round off nuts, espe-

cially if they are held in poor alignment to the fitting.

Their advantage is access from the side of the fitting

when access from the end is difficult. They also gen-

erally allow a more flush fit against surfaces adjacent

to the fitting, so are well suited to low-profile nuts

and bolt heads.

Box-end wrenches enclose the fitting and contact

it at six points, reducing the likelihood of rounding

the fitting under heavy load or poor alignment and

fit. Their limitation is with low-profile fittings, or fit-

tings with no access from the end. Box-end wrenches

come in six-point and twelve-point configurations. The

six-point configuration is more durable and has better

purchase (surface engagement), but twelve-point

wrenches are quicker to get positioned on the fitting.

1.11 Open-end wrench on top, box-end wrench below.

Ratchet drives enable working faster because they

do not require removal of the wrench on the return

stroke. Good applications of a socket and ratchet drive

include crank-arm bolts, brake-mounting nuts, axle

nuts, and seat-post binder nuts.

Socket wrenches (which can be fitted to a ratchet

drive, torque wrench, or socket driver, or may come

prefixed on certain spanners) are similar in their ad-

vantages to box-end wrenches, but even more useful

when there is limited or no side access to the fitting,

such as with crank-arm-mounting bolts.

1.12 Six-point socket (left) and twelve-point socket (right).

Torque is a measurement of a forces tendency to

produce torsion and rotation about an axis, used most

often in bicycle mechanics to describe the tightness of

You're Reading a Preview

What's Included?

Fast Download Speeds

Online & Offline Access

Access PDF Contents & Bookmarks

Full Search Facility

Print one or all pages of your manual

$36.99

Viewed 63 Times Today

Loading...

Secure transaction

What's Included?

Fast Download Speeds

Online & Offline Access

Access PDF Contents & Bookmarks

Full Search Facility

Print one or all pages of your manual

$36.99

This is a comprehensive Bicycle Repair Manual covering all aspects of bike repair. The manual contains 685 pages filled with detailed information and blown-up diagrams.

- Basic Mechanical Skills

- Tapping Bottom-Bracket-Shell Threads

- Facing the Bottom-Bracket Shell

- Reaming and Facing the Head Tube

- Milling the Fork Crown

- Sizing and Threading Fork Columns

- Seat Tube Milling

- Frame and Fork Alignment and Damage

- Adjustable Bottom Brackets

- Cartridge Bearing Bottom Brackets

- Headsets

- Adjustable Cone Hubs

- Cartridge Bearing

- Wheel Building and Rim Replacement

- Wheel Truing and Repair

- Wheel Removal, Replacement, and Installation

- Tires and Tubes

- Taper-Fit Crank Arms

- Cottered Crank Arms

- One Piece Cranks

- Chainrings

- Pedal Removal, Replacement, and Installation

- Freehub Mechanism and Thread On Freewheels

- Chains

- Chainline

- Handlebars, Stems, and Handlebar Extensions

- Seats and Seatposts

- Shift-Control Mechanisms

- Derailleur Cable Systems

- Rear Derailleurs

- Front Derailleurs

- Brake Levers

- Brake Cable Systems

- Cable Operated Rim Brake Calipers

- Hydraulic Rim Brakes and Disk Brakes

- Suspension Forks and Rear Shocks

Total Pages: 685

Format: PDF

Language: English

Compatible: Win/Mac

This manual is useful for both professional mechanics and DIY enthusiasts. It contains numerous pictures and diagrams, and all pages are printable for convenience. Save money by performing your own repairs with these easy-to-follow, step-by-step instructions. Instant access means no shipping costs or waiting for a CD to arrive in the mail. For any manual-specific questions or needs, feel free to email us, and we will be happy to assist you promptly. Thank you for visiting our homepage on tradebit.